The China Diviner

A popular chart for China plots metals prices against the credit impulse. But we'd argue that even in China, it is useful to look at the price of money not just the quantity, with interest rates leading credit. The relationship has weakened since 2020, but that tells us about what ails the cycle.

The importance of interest rates

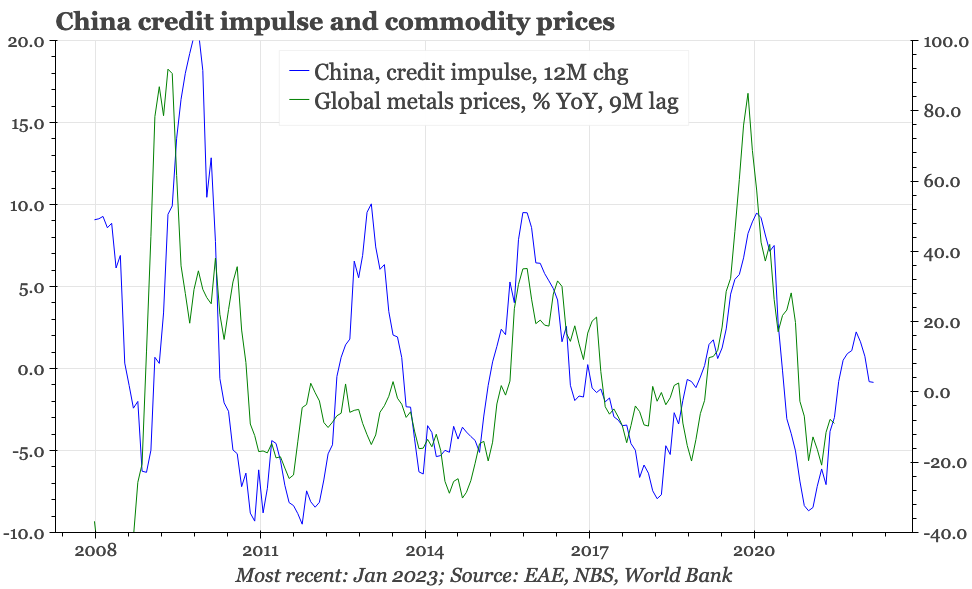

Perhaps the most popular global macro chart for China plots global metals prices against China's credit impulse. The relationship is reasonably tight, and as the usual thinking goes, so it should be. Monetary policy in China focuses on changing the quantity of money not the price, and China's domestic cycle is driven by construction and so demand for commodities.

Whether based on the chart or the intuition, there is certainly something to this. Currently, the credit impulse has bottomed out, suggesting the deflation in global commodity prices of the last 12M now reverses somewhat. As the market struggles to work out the global inflation, this is a signal worth paying attention to.

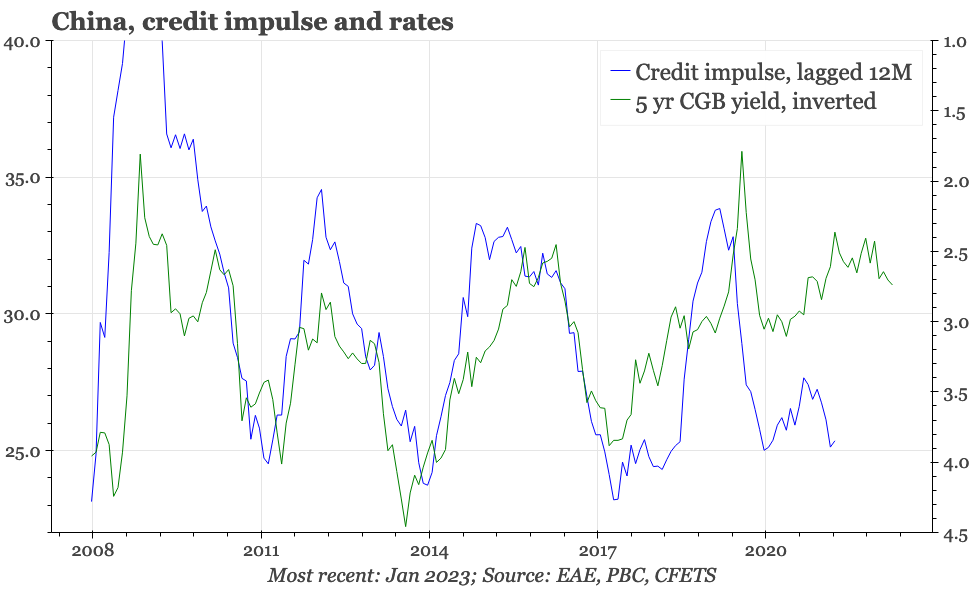

But, if the idea is to get a good lead on the direction for the economy, why not use interest rates instead of credit? If there is a tight relationship between credit and metals prices, there is also a strong correlation between interest rates and credit. Moreover, investors only ever know the credit numbers when the data are released while interest rates, arguably, tend to be leading indicators. In short, if investors want to get a sense of where China's cycle is going, they should be looking at Chinese interest rates more than just the credit impulse.

Understanding the obsession with quantity

Seemingly, the reason this observation isn't more widely appreciated is that it doesn't fit with the popular understanding of how China's policy and financial system works. Monetary policy targets in China have involved quantity, not price. Historically, that was M2 growth and explicit credit targets. The system of formal credit targets for individual banks was ended in the 1990s, but the spirit lives on, through window guidance, less formal credit quotas, and myriad macro-prudential rules.

For global macro investors, there is also the ingrained memory of 2008-09, which is remembered as a sequence: first came enormous monthly credit numbers, and then strong economic recovery. So, from both a formal policy point of view and a practical perspective, the markets have been conditioned to think that the variable that matters most in China is the quantity of credit.

In many ways, however, 2008-09 was the exception, not the rule. In common with its counterparts elsewhere, China's government was thrown into a panic by the global financial crisis, resulting in a policy aggressiveness that hasn't been repeated – even in the proper recession that China experienced in 2022.

Rates as a policy tool

That top-down desire to get things going fifteen years ago was aided by a financial system that still bore a lot of the imprint of the centralisation efforts of the late 1990s and early 2000s. That gave the authorities some ability to control lending growth in the run-up to 2008, but also the power directly to turn the credit taps on when crisis hit.

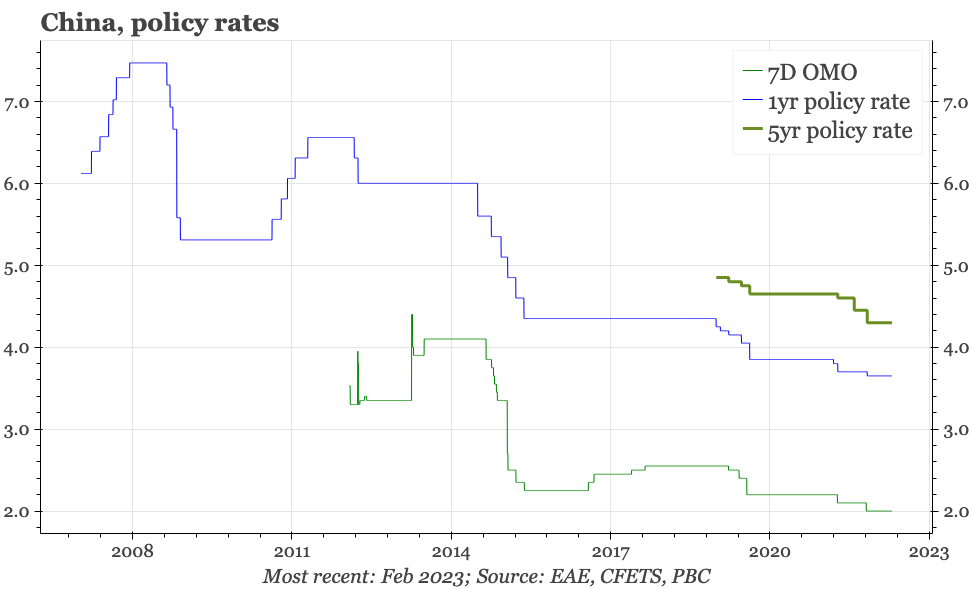

Even then, though, interest rates were a key part of the policy reaction. After being hiked by a bit over 200bp as the economy warmed up in the years between 2004 and August 2008, they were then cut by just as much in the following five months. Interest rates were then raised when the economy recovered in 2010-11, and were subsequently cut again as activity lost momentum once more.

Changes in the reserve requirement are also a usual part of the policy response to shifts in the economic cycle, and the government is always making direct efforts to boost – or restrict – lending. But interest rates too are an essential and usually ever-present part of China's monetary policy. That wouldn't seem necessary if direct manipulation of monetary aggregates was effective. In work elsewhere, we've shown how the transparent components of China's monetary policy – interest rates and the RRR – are manipulated in response to changes in prices, activity and money supply.

Why rates matter

Arguably, the financial system should have become more sensitive to rate changes in the years after 2008, as the centralisation of the 2000s gave way to the pluralisation and shadow banking of the 2010s. This shift was in large part driven by banks trying to escape the quantitative straightjacket that regulators still tried to tighten around the traditional banking sector. To the extent that the banks succeeded, they thereby undermined the effectiveness of the government's continued direct efforts to manipulate the supply of credit.

Beijing's regulators eventually caught up with the shadow banking system, and this successful pursuit at the margin would have increased the effectiveness of the authorities' quantitative tools. It is also true that a lot of loan demand in China, whether in the past or now, is from state-sector entities, which face soft budget constraints and thus have loan demand functions which are less sensitive to changes in the price of credit.

But local governments and state-owned enterprises aren't the only drivers of financial developments in China. Households, through both borrowing and investing, are also important actors. As the source of almost all the end-user demand for property, they also play a particularly out-sized role in the real estate sector, which in turn has driven most of China's economic cycles for the last twenty years.

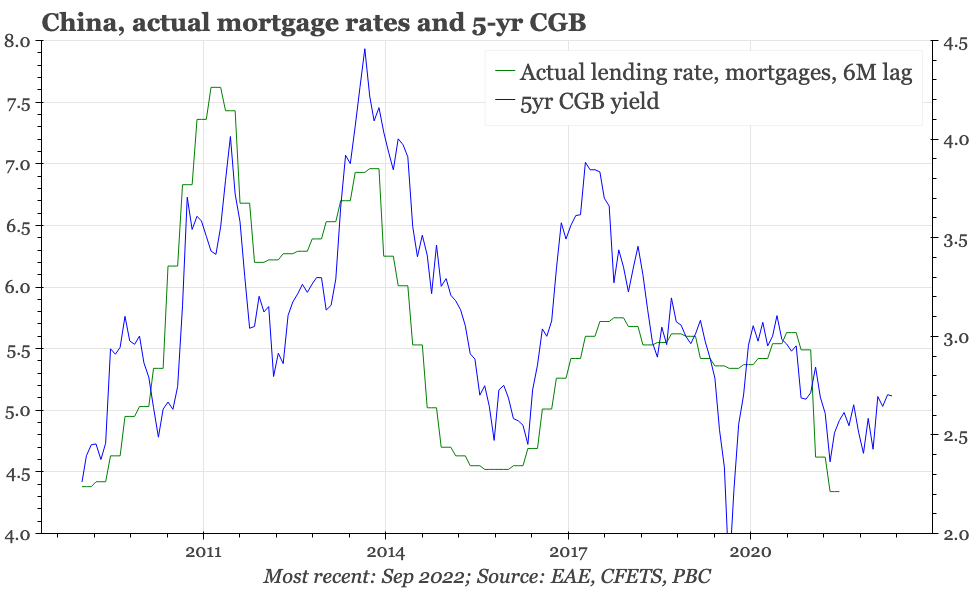

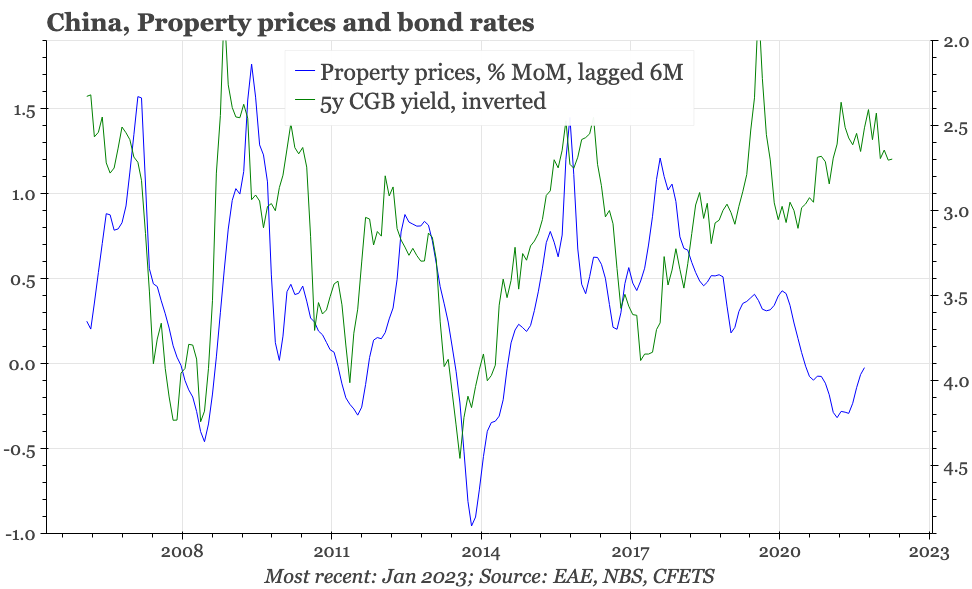

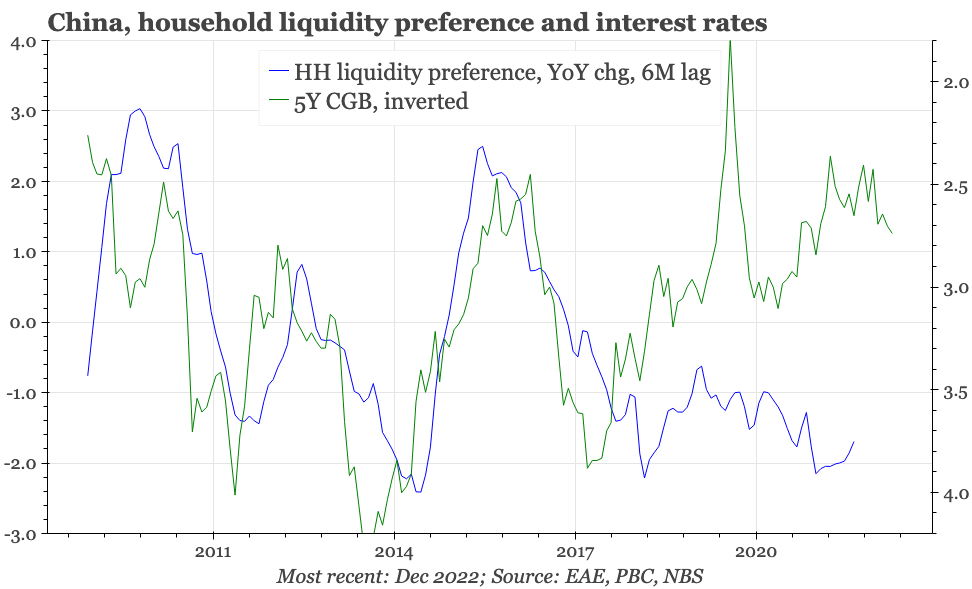

Households don't have the luxury of the perceived government backstop that underpins the soft budget constraint in the state sector. As a result, household financial behaviour, as would be expected, does tend to be sensitive to changes in interest rates. So, for most of the last 15 years, there has been a decent correlation between interest rates and both mortgage lending and property prices. But in China, it isn't just the borrowing decisions of households that impact the economy. Because households are such big savers, how they choose to invest their spare cash is also a financial flow that impacts the strength of the overall cycle. There is evidence that interest rates matter here too.

Implications

You don't need to be overly eagle-eyed to observe from the charts that the relationship between interest rates and all the cyclical indicators has gone awry since 2020. Interest rates fell steadily for most of 2021 and 2022, with the 5-year CGB yield reaching under 2.5%. Based on previous relationships, that would mean the economy and credit growth should be booming by now. Clearly, they aren't.

There's been at least two developments since 2020 that can explain this disconnect. Covid, and the government's response to the disease, meant the usual policy signals couldn't work in the way they would usually have done. Clearly, with activity in the economy depressed, companies wouldn't be taking advantage of the low level of interest rates to take out loans for expansion. Just as importantly, in 2021 there was the regulatory squeeze of property developers, seemingly the first example in the modern history of China's real estate markets when macro-prudential measures alone have caused a downturn in the sector.

This doesn't mean the interest rate perspective has lost relevance. Apart from anything else, it highlights the risk of a structural regime change in China's economy and financial markets, a shift that doesn't show up in the that the credit impulse chart. Put another way, the lack of engagement with the fall in interest rates suggests it will be much more difficult to get a revival of the credit impulse than many global investors are probably assuming.

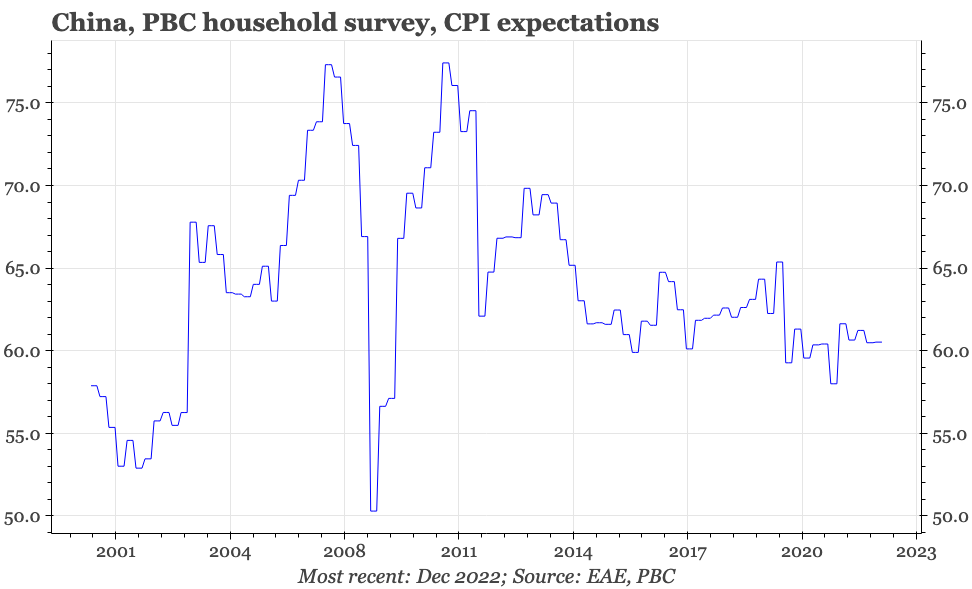

If China's biggest macro challenge is instead cyclical rather than structural in nature, then the focus on interest rates helps to identity what exactly that is. If falling nominal rates aren't effective at boosting growth, then it implies real rates are too high, and that policy needs to focus on raising inflation expectations. The government, in its own way, recognises this, with frequent mentions in recent policy statements on the need to raise "confidence". That is encouraging, though for the moment, it is difficult to see what in tangible terms the government is doing in this regard.

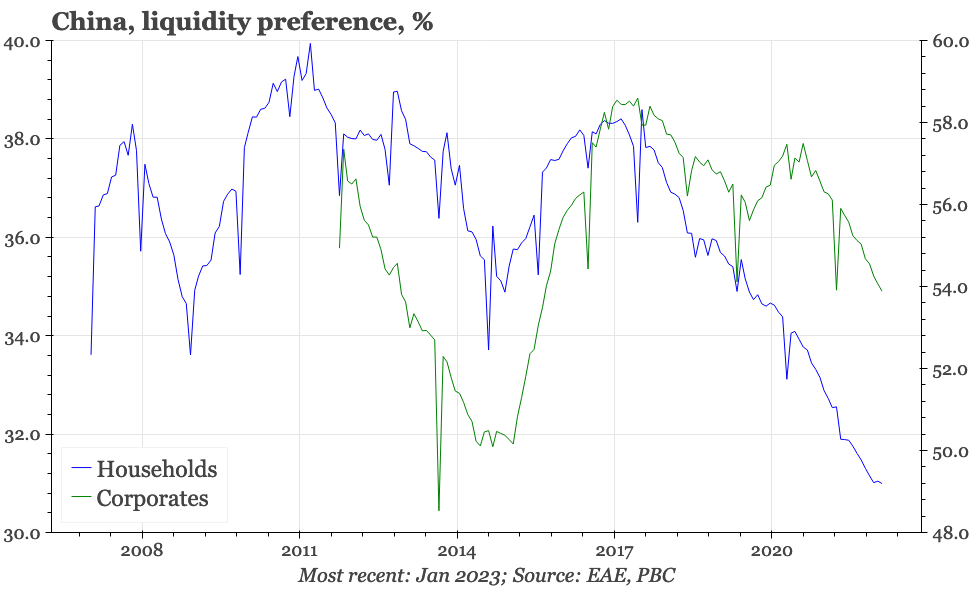

The importance of real rates leads us to think that right now, there's a couple of particularly important indicators to be following. First, the proportion of household savings held in time deposits, which is at a record high, and very consistent with the idea of high real interest rates. If this starts to reverse as a trend, it will be positive for a sustained recovery of activity. Second, indicators of inflation expectations, with the official measure being updated with the release – perhaps in March – of the PBC's Q1 urban depositor survey.