Region – export trends and market implications

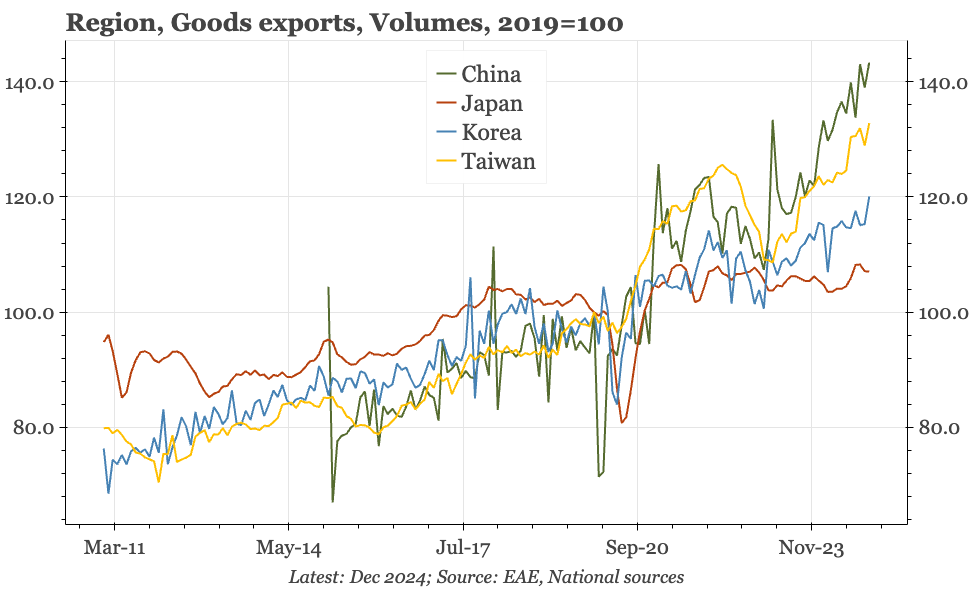

In LCU terms, there's little to choose between exports in the different economies. But in volumes, China and Taiwan are very strong, and Korea and Japan clearly lagging. This should have implications for CNY, TWD and KRW. For Japan, the significance is for macro if USDJPY turns.

China. PBC intervention has been preventing the CNY weakening. It is easy to see $CNY moving higher if Trump goes all in on tariffs. But absent either of those two forces, it isn't clear that the market would force a big depreciation. The weakness of import growth and domestic demand argues for more loosening, but China's remarkable export strength suggests the currency is quite weak enough.

Japan. In local currency terms, Japan's exports look as strong as those of the rest of the region. But that's all because of JPY weakness: export volumes are doing nothing, with little evidence that Japanese firms have cut USD prices to gain market share. The implication is clear: revenue growth for the manufacturing sector will be hit hard if and when the JPY really turns.

Taiwan. Semiconductor demand, on the back of covid and then AI, is giving Taiwan's export sector a lift not seen in 20 years. That's clearly being reflected in the enormous and trade and current account surpluses. The case for a structural appreciation of the TWD looks as strong as ever. Will Trump (or more likely Bessent) start to push in this direction?

Korea. While SK Hynix is seeing the same strength that's lifting Taiwan's tech sector, Samsung has been left behind. And while semi accounts for 50% of Taiwan's exports, in Korea the ratio is just a fifth, meaning the weakness of non-tech also matters more in Korea. As the BOK has made clear, this underperformance is in part the flipside to the strength of China's exports. Continued underperformance of KRW relative to TWD can be expected.

Regional export patterns

In local currency terms, exports across all the economies of East Asia have been strong. Shipments rose by around 40% between early 2020 and mid-2022. There's been some differentiation since, with Taiwan's TWD exports rising more quickly than elsewhere. But the other three economies have also seen clearly seen another wave of export advances since mid-2023.

This export growth hasn't been on the back of aggressive cuts in USD export prices. Prices are down from the 2021 peaks, but don't look particularly soft when looked at over a broader time frame. If there is an exception, it isn't China but rather Japan, though even here, there's no real evidence of aggressive price cuts.

It is in the other components of export earnings that the differences between economies are clearer. Japan is at one extreme, with almost all the strength in JPY exports being the result of the depreciation of the currency against the USD. At the other is China – and to an extent, Taiwan – where the strength in export earnings is largely the result of increases in volumes.

China

In China, the strength of exports really is remarkable, especially when viewed in the context of sluggish global demand. Indeed, in the last 30 years, China's relative export performance in recent months lags only the early 2000s. Then, the growth was driven by entry to the WTO. This time, it is the result of industrial policy, big increases in manufacturing investment, and a government focused on achieving self-sufficiency.

The strength in China's exports is broad-based. In 2024, volumes grew in 91% of the 98 standard 2-digit Harmonized System trade categories. Admittedly, that followed a somewhat sluggish 2023, but even then, volumes had grown in 71% of all the HS categories. Across these individual categories, export growth has averaged 13% in the last couple of years, a period during which global import demand has barely grown at all.

China's trade performance in the last few years stands out in one more way, but that is because of exceptional weakness rather than remarkable strength. The usual pattern before 2020 was for imports and exports to grow together, even if export growth was more often stronger. But that relationship has now completely broken down. While export volumes are now 50% higher than in 2019, imports have barely grown at all.

With China previously a big source of demand for the rest of East Asia, the stagnation of imports clearly matters for the other economies. Korean and Japanese exports to China are now barely higher than they were in 2017. Even for Taiwan, where shipments to China look a bit better, they are still 30% below the peak of 2022.

This in turn feeds through into trade and current account balances. Korea is now running a trade deficit with China, which is a big change from the bilateral surplus of 4% of GDP just a few years ago. Taiwan's trade surplus has fallen more sharply, but it hasn't disappeared. And Taiwan's overall trade surplus is now bigger than ever, with the drop in the China component more than offset by a much bigger surplus with the US.

Korea and Taiwan – tech

Taiwan is the only other economy that comes close to China in terms of the trend in exports. That strength was first apparent in the pandemic surge in shipments, but after the pause in 2H22, Taiwan's export volumes have increased quickly once again, suggesting that the shift is more structural than cyclical. Taiwan is gaining share in all major overseas markets, including China itself, the US and the EU.

It is at the headline level where Taiwan's exports are comparable with China's. In the details, the story is very different. Whereas export strength for China is broad-based, for Taiwan, it is all about semiconductors. That is also true for the rebound in Korea's exports since 2023. That is unusual: historically, upcycles in exports in both Taiwan and Korea have tended to be seen across product categories.

The strength of semi is much more visible in Taiwan than Korea. That can be illustrated in several ways. Taiwan's semi sector is riding the AI wave in a way that isn't true in Korea. TSMC's earnings are surging relative to the performance of Samsung (Korea's SK Hynix is doing better, but it is a much smaller firm). Taiwan's semi prices are holding up, whereas for Korea, prices are down. Finally, Korea is now in a more subordinate position in the semi supply chain, exporting more to Taiwan as, in some ways, it becomes a supplier to TSMC.

Korea's semi troubles are partly because of competition from China. That's been a theme of recent press reports, but was also specifically highlighted in a recent BOK report that noted companies like CXMT and JHICC selling lagging-edge DRAM chips at 50% of market prices. With China previously the big market for Korea's own older-generation semis, that competition in turn explains a second phenomenon highlighted in the BOK report: the fall in the share of Korea's semi exports going to China.

Korea and Taiwan – non-tech

Outside of semis, there isn't much sign of strength in Taiwan's exports either. But for Taiwan, that doesn't matter for this cycle. Together with servers – which for export include the value of the chips embedded in the machines – semis account for 50% of Taiwan's exports. So strength in TSMC's sales are enough to lift Taiwan's overall exports (production at the overseas fabs of Taiwan's largest firm aren't yet significant enough to matter).

Korea's export base is, by contrast, much broader. Semi is usually the biggest sector, accounting for 21% of total exports in 2024. However, the degree of its dominance depends on the DRAM cycle, and other sectors are significant too: autos are around 15%, and steel, refining and non-semi tech each with around 6-7%. Even if Samsung was booming, Korea's overall export performance would still be held back if there was no momentum in these non-tech sectors.

The headwind for Korean traditional industry, apart from the general weakness of global demand, is once again, China. Domestic demand in China has been weakened by the collapse in property market activity since 2021. But there's also import substitution as China's own manufacturing industry gains competitiveness. Japan and Korea also seem to be suffering from a reorientation of China's supply chains away from North Asia and towards ASEAN.

In third markets like the US and EU, China isn't obviously eating into Korea's market share. However, the BOK argues that the competition from China is driving down prices, and so contributing to the weakness of Korean steel and chemical exports. Again, that deflation isn't apparent in overall export prices from China, and nor is it obvious in detailed data for Korea. Still, the point remains: the rise of manufacturing in China is a big reason for the weakness of Korea.