China - weekly update

The government, fearing inflation or perhaps CNY weakness, is stepping up easing, but trying rather furtively.

Furtive easing

The PBC was unusually communicative last week, issuing no less than three statements discussing the economy. None of them included specific new commitments, with the tone instead being summarised by the concluding remarks of the last statement on Friday that "on the foundations of conscientiously implementing the policies already announced, to further step-up the work intensity, further increase the level of support for the real economy, ensure the stability of the market, the stability of the economy, and create a good environment for the successful convening of the 20th party congress".

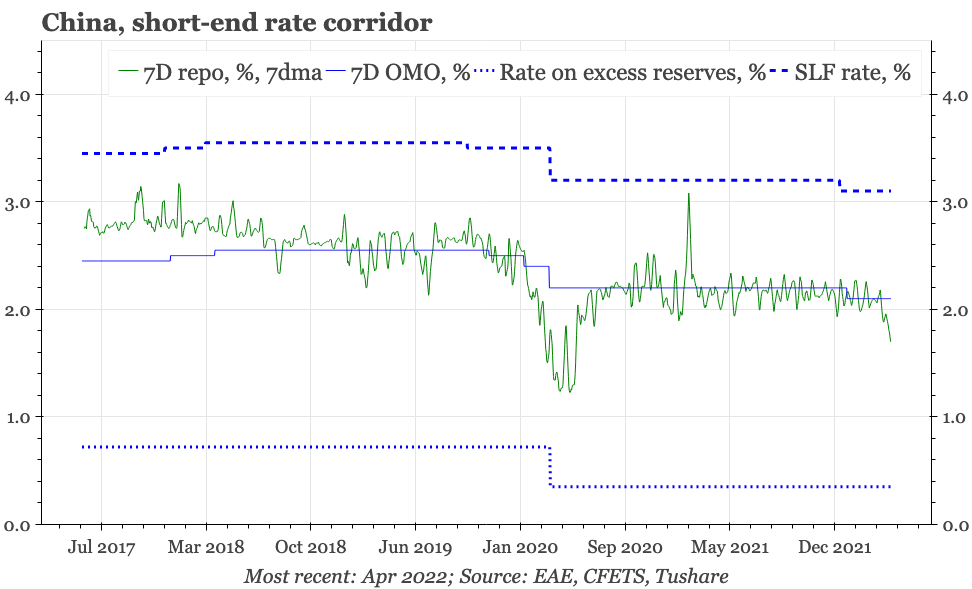

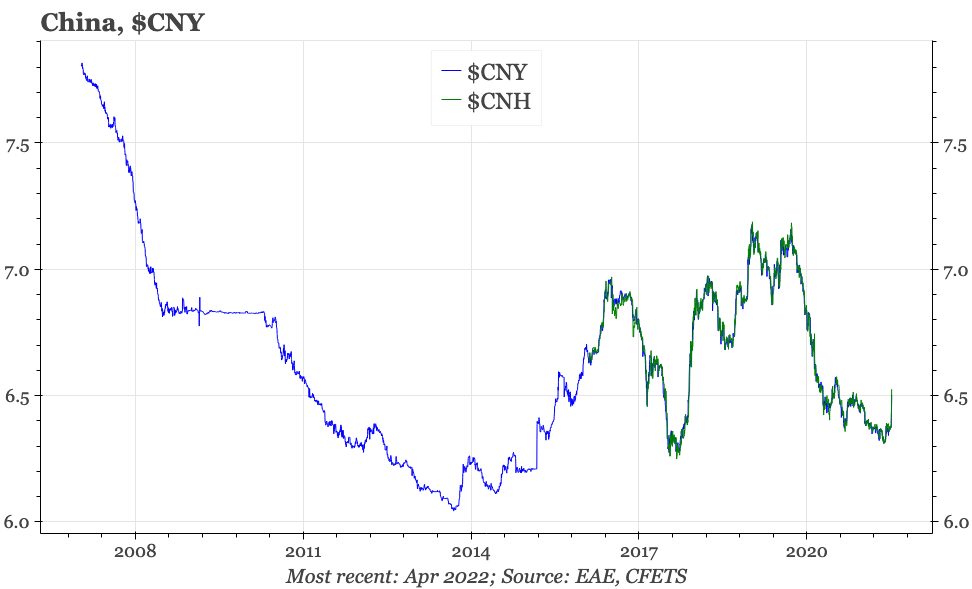

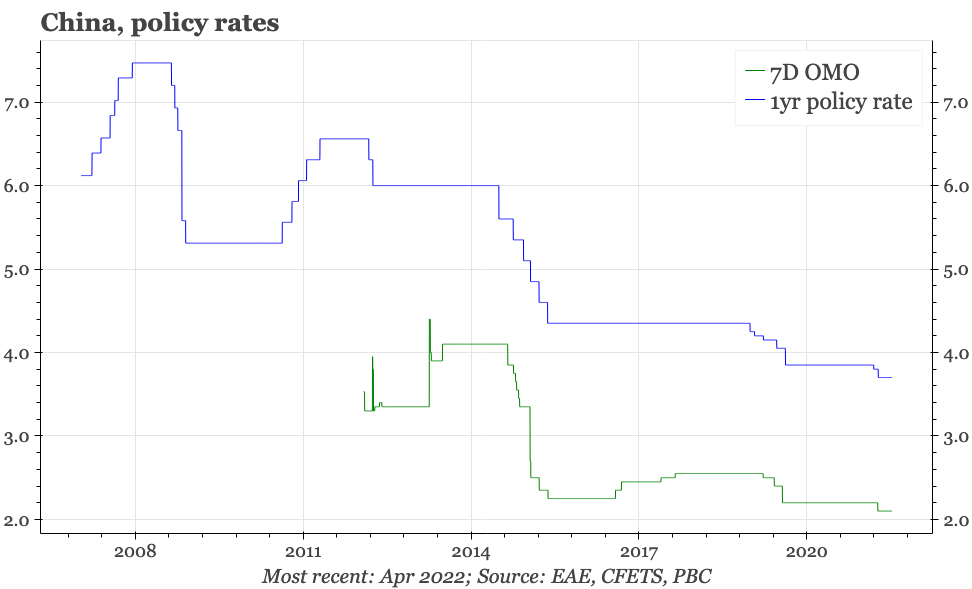

While not being repeated quite as often as they were last week, these sentiments have been expressed a few times in recent months. But this time, while not admitting to it publicly, the PBC did add some substantive backing to its policy direction, allowing - if not also encouraging - some important market shifts. So, in the second half of last week interbank market rates were pushed below the official 7-day open market rate; there was news that several commercial banks had responded to earlier guidance from the PBC and cut deposit rates; and, perhaps most significantly, the RMB started to depreciate against the USD.

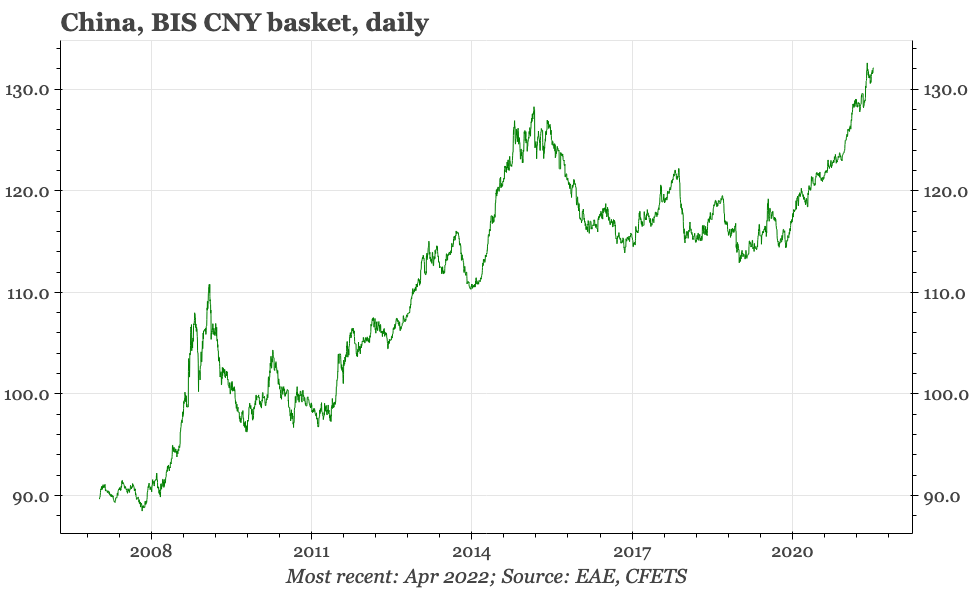

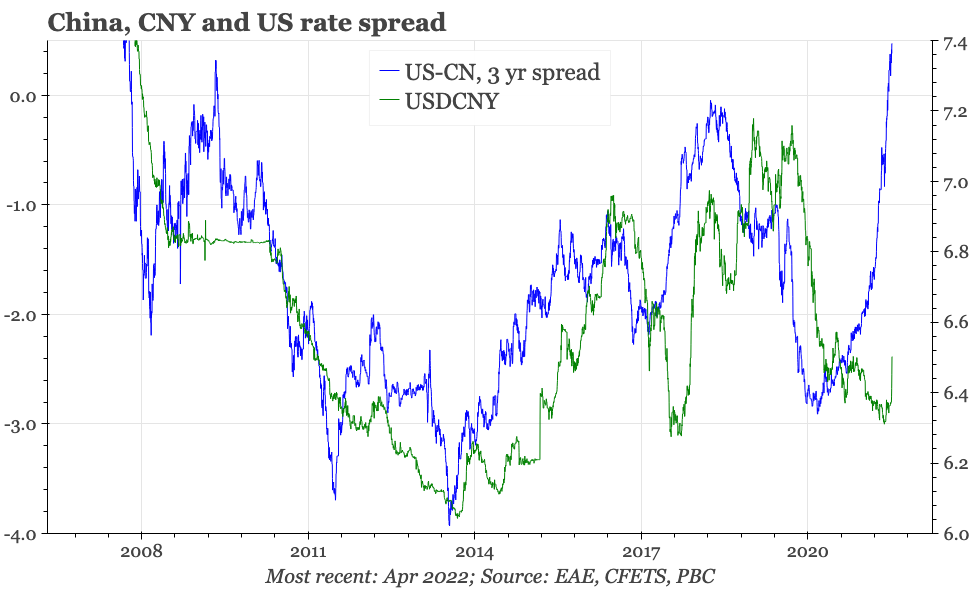

The move in the CNY is belated, given there's been evidence of capital flows out of China for at least the last couple of months, and yet both against the USD and on a basket basis the currency has remained stubbornly strong. The emergence of capital flows are consistent with the big shift in interest rate differentials between the US and China, as well as the divergent monetary policy rhetoric from officials in the two economies.

The backdrop for this divergence is the very different economic activity and inflation trajectories of China and the US. In terms of economic growth, the big immediate drag in China is the ongoing attempt once again to eradicate covid. Over the weekend that task threatened to get a whole lot harder than it already was. The official count in Shanghai remains high, but at a bit under 20,000 cases yesterday is at least (slowly) falling. But there's also now the beginnings of an outbreak in Beijing. The official count remains small at just 14 cases yesterday, and the official reaction in the city has been in the form of widening PCR tests not lockdowns, but residents are fearing there's worse to come, with panic buying in supermarkets.

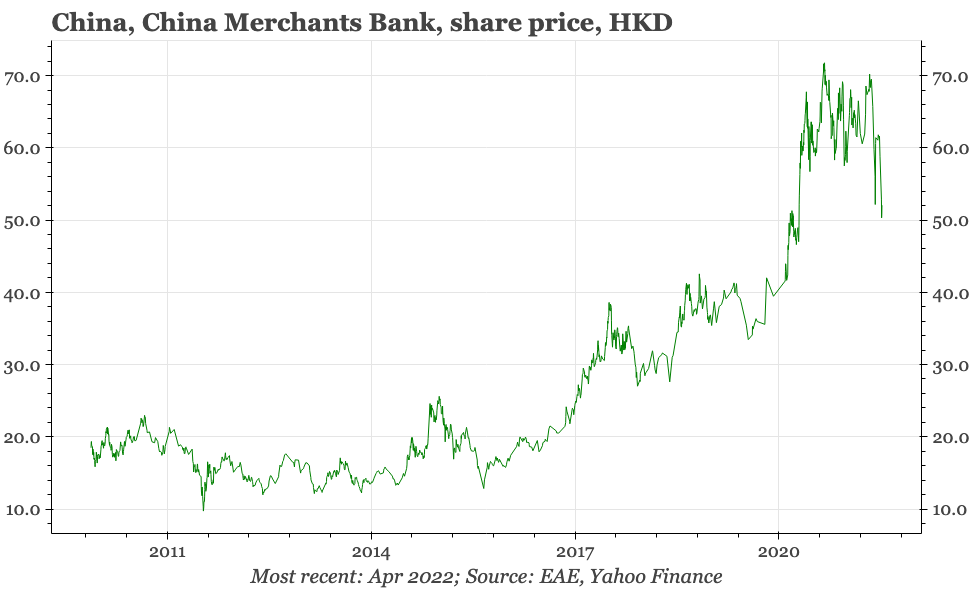

Needless to say, there will be no stabilisation of the economy if one big important city after another goes into lockdown. But this isn't the only headwind facing the economy. Among other pressures, there's also ongoing corruption investigations in the finance industry, with the latest target being top officials at China Merchants Bank, which - until now - had looked like one of China's more successful financial institutions.

The broad range of issues facing the economy and markets make it very difficult for policymakers focused more narrowly on the economy to ensure fulfilment of their pledge of the last few months to be "cautious in introducing contractionary policies". The one thing that economic policymakers can control - presumably - are macroeconomic policy settings, and so given the cycle has weakened in recent weeks below their full-year growth target of 5.5%, the combination of lower rates and weaker CNY overall seems somewhat predictable.

That does raise the question of why these shifts haven't appeared sooner, and for interest rates in particular, more openly. The PBC has said that the CNY should play a stabilising role in the economy, but there's also been chatter that the central bank has been worried about capital outflows. In theory that concern could explain the recent stability in policy rates even as the cycle has taken a new step down, though if there really is a worry about capital flight, it is hard to explain why the PBC allows a key benchmark rate to fall - even if not a policy rate - just when the CNY moves too.

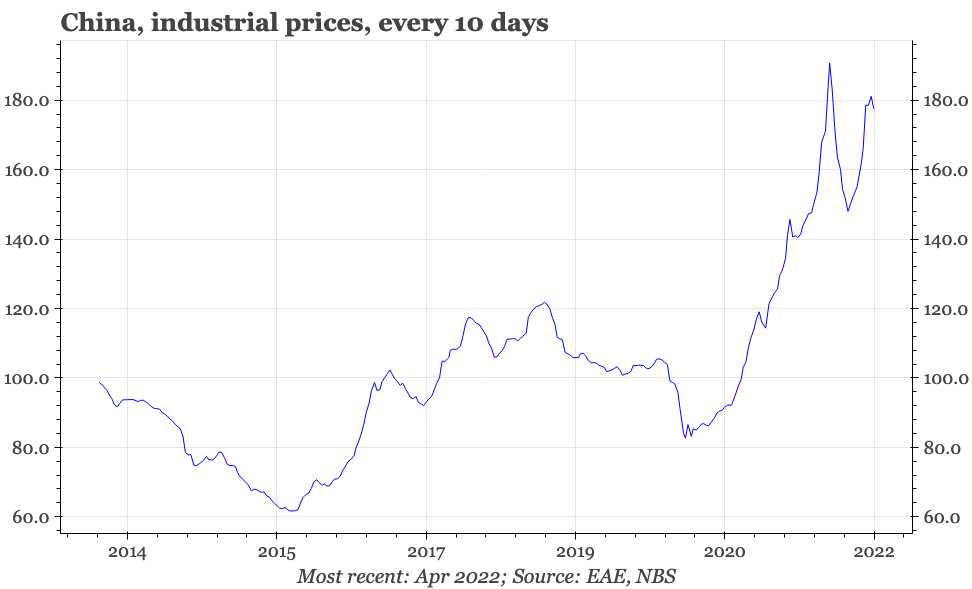

Apart from capital outflows, the other potential constraint on PBC loosening is inflation. Like GDP and activity, price trends in China have looked very different to those in the US: while measured using PPI inflation in China has been strong, on every other metric it has been weak. However, some worries about prices are now starting to appear in policy statements, with the PBC's statement on Friday including a pledge to "prioritise and energetically support agricultural production as well as output and the smooth supply of coal, oil, gas and other important commodities, and ensure the stability of prices".

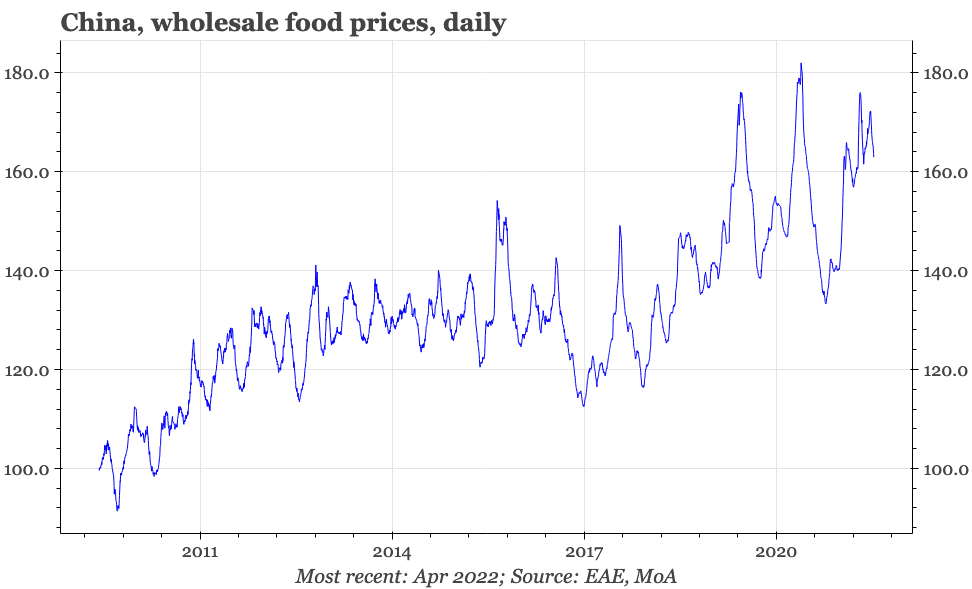

Given that these concerns about prices have only started to appear very recently, they would seem to be driven by the supply disruptions caused by the covid lockdowns more than a worry that China is starting to see the same inflation dynamics as much of the rest of the world is experiencing. This could change, but even with covid it doesn't yet look like inflation is becoming a huge problem. Food prices were unseasonally strong through the first half of April, but at least according to the Ministry of Agriculture, have started to fall again in the last couple of weeks.

It is probably still reasonable to assume that there will be somewhat more concern about inflation from policymakers in Beijing as long as covid control remains the number one priority for the government, and thus that lockdowns and other restrictions remain a risk for the economy. It is probably also true that now the currency is moving, the central bank will likely want to see how much momentum that trend has before itself adding actual rate cuts that would threaten to fuel the downside. Overall though, the poor state of the cycle still suggests there is more easing to come.