China – third time...unlucky?

The population is starting to chafe against lockdowns, but isn't prepared for opening. The compromise path forward is rising covid cases signalling more eventual openness, but lockdowns continuing to be used to try to slow the spread of the virus. That's a very messy path for financial markets.

Taking stock

The government gets stymied

In November, it had been looking like the authorities were seeking to cast off the issues that had so heavily weighed on China the last couple of years and start to move forward. Xi Jinping re-appeared on the international stage, and seemed to be pushing for an improvement in US-China relations. There's now a stronger sense that the 16-point package of measures reported by media a couple of weeks ago is part of a concerted effort to stabilise the property market. And there was the 20-point package of covid measures, aimed at rolling back some of the excesses that have resulted from the government's strategy to try to keep the virus at bay.

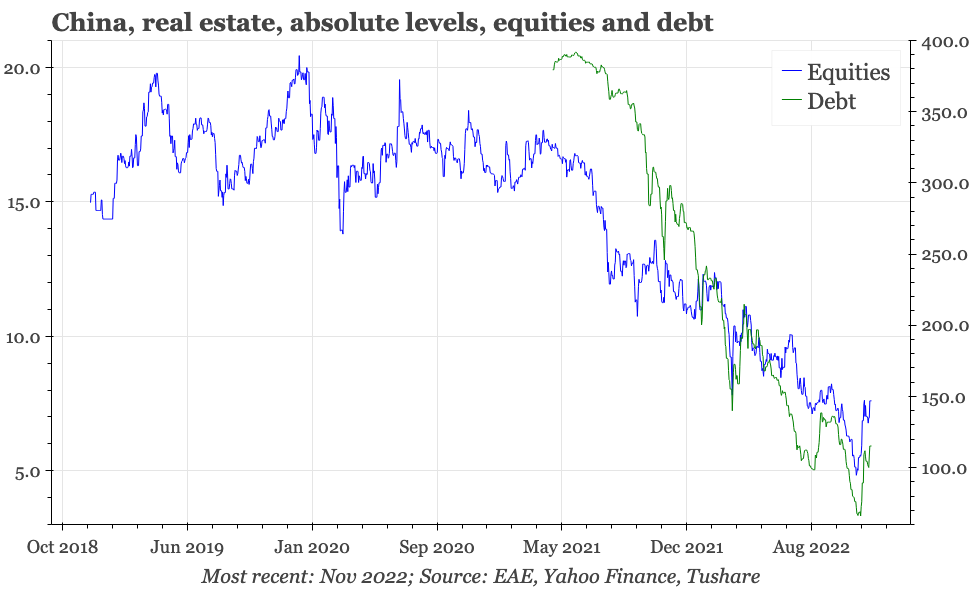

On the first two, there have been signs of progress. US-China contacts have started up again, a development that has been helped by the Biden Administration also taking steps to put a floor under the bilateral relationship. Financial market sentiment towards property developers remains poor, but has experienced the biggest bounce in quite a few months.

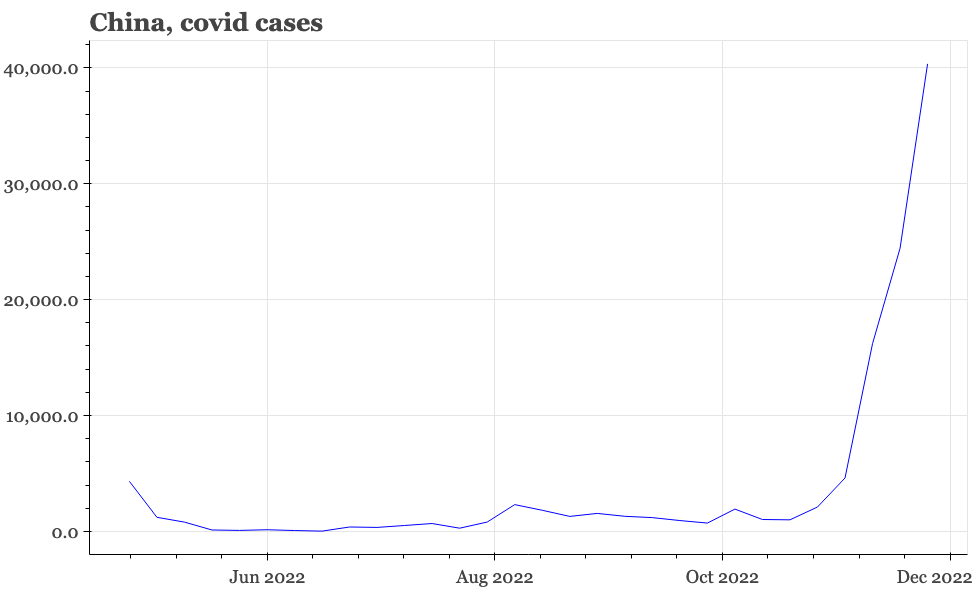

However, and perhaps needless to say, progress on covid policy has been much less straightforward. Indeed, the authorities have dug themselves into quite the hole. The 20-point package in itself was never aimed at ending zero covid. But the relaxation allowed by those measures probably encouraged a rise in covid cases that was anyway in the works. The sharp increase in case count quickly prompted a re-imposition of restrictions that had been relaxed just days before.

All about covid

Those measures will have been damaging for the economy through November, and we'll get some sense of how just painful they've been with the release of the PMIs on Wednesday. But the restrictions haven't been strong enough to bring covid back under control. As of yesterday, the national case count had reached more than 40,000, higher than recorded even during the Shanghai lockdown. Moreover, there's no sign that the rise is slowing down. Around 10% of the 4,000 cases recorded in Beijing yesterday were in people outside of quarantine, meaning spread of the virus is continuing.

So, China now has the worst of both worlds: restrictions that are powerful enough to damage the economy, but not strong enough to control fully the spread of the virus. That would be bad enough. But the situation has deteriorated further over the weekend. Protests have broken out across different cities in China, with segments of the population starting to chafe at the apparently never-ending covid restrictions.

In themselves, protests aren't unheard of in China. But usually, they are localised affairs, triggered by an event in a particular region. As such, they tend not to attract the sympathy or support of residents elsewhere in the country. By contrast, the protests of the last few days have sprung up in several cities across the country, and are expressing opposition to a national policy – namely covid zero. The protest sites have included university campuses, which matters given students have been drivers of all the big protest movements in modern Chinese history. Some of the protests have even included direct criticism of Xi Jinping.

The third political covid crisis

To be sure, the protests remain small-scale and spontaneous, with no sign of any over-arching coordination. And, before assuming that they signal impending revolution and the overthrow of the CCP, it is worth remembering that there's been a couple of other occasions when covid has looked like triggering political problems for the party: first with the death of the Wuhan doctor Li Wenliang whose warnings about covid had been ignored, and then with the Shanghai lockdown. On neither occasion did the speculation of impending doom for the party come to anything.

This time might be different. It certainly doesn't seem that the authorities have easy ways to reduce the tensions that are currently boiling over. Indeed, if the government is facing a clear policy choice, it is between doubling down and reimposing harsh lockdowns – with the dual aim now of stopping both protests and covid – or recognising that the battle to suppress covid has finally run its course, and starting to move towards real opening.

Neither looks like an attractive option. Given the way the party works, the knee-jerk reaction would probably be to reach for more oppression. As a first step, that at least seems highly likely to push back against the anti-lockdown protests. But at least in terms of more general covid policy, there is now an obvious risk that popular tolerance for lockdowns has reached breaking point, and that is a threat that even the CCP would seem to need to be sensitive to.

At the same time, given the way omicron spreads, not locking down now would likely mean a further dramatic rise in covid cases. Unfortunately, the country is very ill-prepared for this eventuality. There's been no change in the official rhetoric that barely hides China's official scorn for other governments that have chosen to “live with the virus”. Consistent with that, practical preparations for a life after zero covid also look to have been terribly insufficient, with recent data showing that just 65.7% of those aged 80 and over have received two vaccinations.

More messiness ahead

Given all this, there's no obvious way forward. The risks seem to be tilting in favour of opening, but a messy, reluctant one. With the vulnerabilities in the population and the healthcare system, the authorities can't afford to just let go. There doesn't seem now to be any way to get covid cases back to zero, but the government seems to have little choice but to try to slow the continued rise with lockdowns and restrictions.

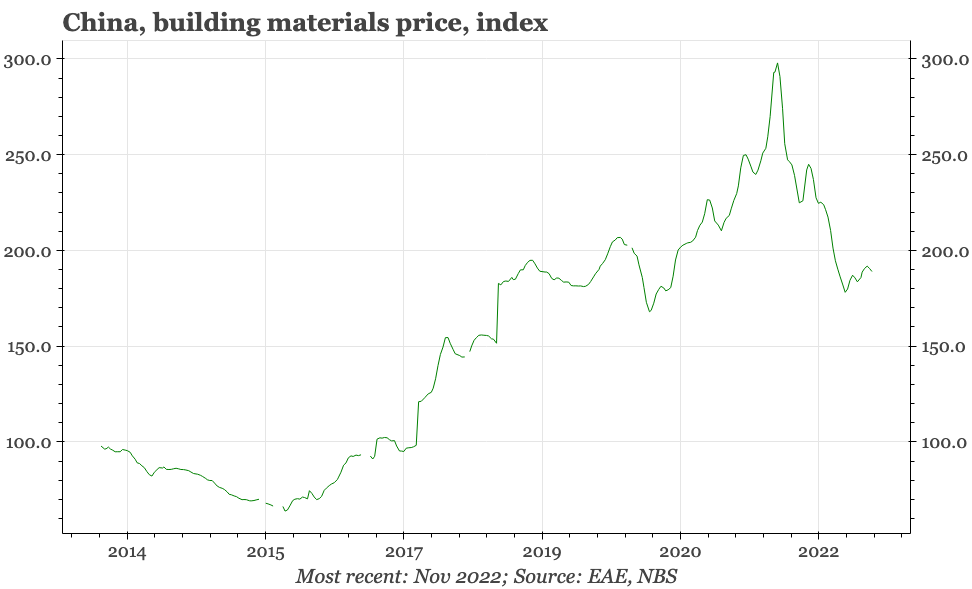

That might be enough to diffuse some of the tensions that have emerged in recent days, with residents fed up with restrictions perhaps able to sense some light at the end of the tunnel. But for economic activity, it feels like a bad scenario, where the economic pain of lockdowns and restrictions continues to be felt well into 2023. That in turn will make it more difficult for the government to achieve its other policy aims, including the stabilisation of the property market.

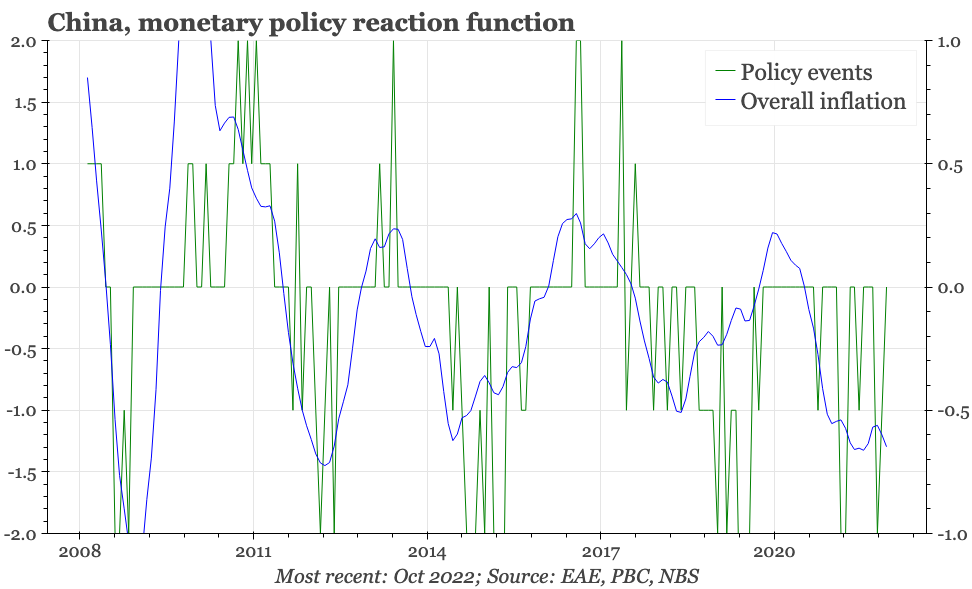

Perhaps the markets will also be able to see through this valley, and continue the process of pricing in eventual cyclical recovery, a process that began with the release of the 20-point plan. That seems optimistic if the scenario is going to be a combination of both rising cases and continued restrictions. At least for fixed income, it feels like there's still room for more policy easing, with Friday's RRR cut very much consistent with the PBC's usual reaction function when inflation indicators are as weak as they currently are.