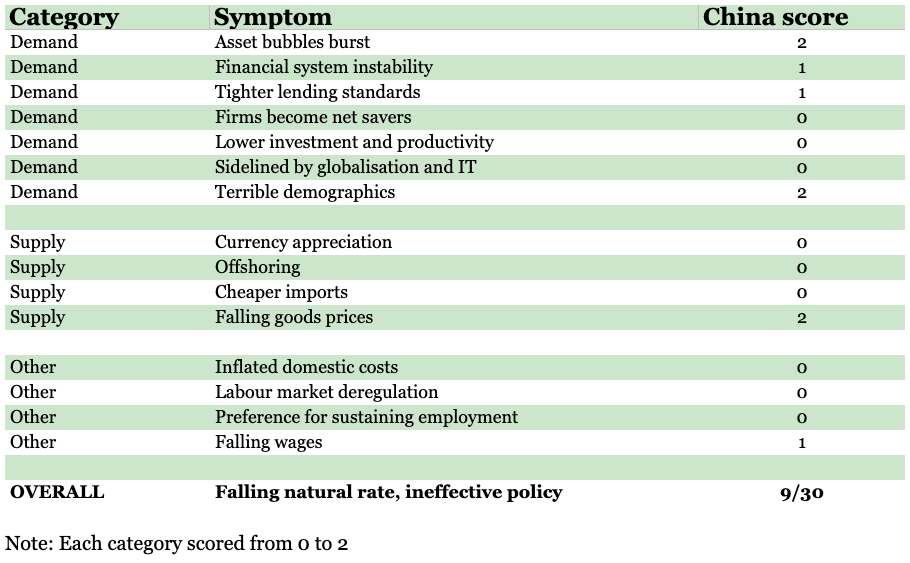

China – on a Japanification scorecard, only getting 30%

With the BOJ's review of post-1990s Japan, we have an inventory for Japanification. Using this to assess China today, what stands out is not the similarities, but the differences. All told, on my scoring China isn't graduating to Japanification, achieving a mark of only 30%.

The BOJ recently published a long, interesting report reviewing economic developments in the last 25 years. Well worth a read, the report makes it clear that Japan's malaise wasn't inevitable, but was due to a particular mix of factors. Certainly, a rebuilding of corporate balance sheets – the famous "balance sheet recession" – was one of those, but there were others too: Japan failing to keep up with the globalisation and IT revolutions of the 1990s, continued currency appreciation even after the bubble burst, an inflated domestic cost base that was exposed as China emerged and import penetration increased, and terrible demographics.

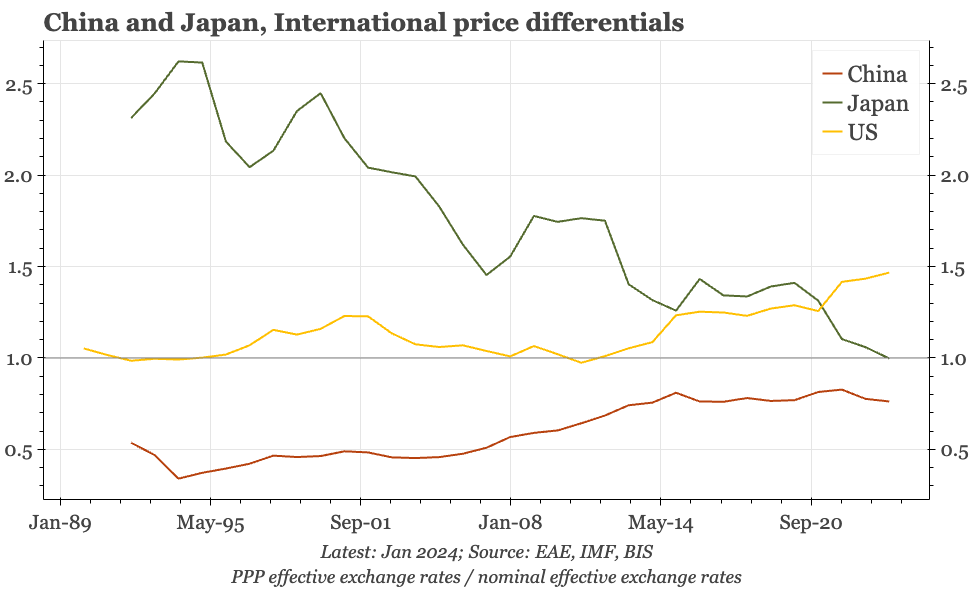

All those can be divided into "demand" and "supply" factors. But the BOJ also identifies a third group, which is less easy to categorise. Those are the ingredients behind the "deflationary mindset", a phenomenon that prompted changes in behaviour that meant once deflation started, it became very difficult to end. The fact that Japan was so expensive in 1989 – and became more so as the JPY surged in the 1990s – meant prices did have a long way to fall. However, that costs could be cut reflected peculiarities of Japan's economic structure: the system of lifetime employment meant there was huge room to make the labour market more flexible. Cultural factors were also involved. As an example, society placed a preference on preserving employment, with the trade-off being wages fell instead.

With all that content, the report has direct relevance for thinking about China today. Essentially, the BOJ has provided a detailed inventory of what constitutes "Japanification", a schedule that can be used to assess current developments in China. The conclusion is that China doesn't really look similar at all. It does have some of the financial stress resulting from the collapse of the property market. But even here, the feed through into the broader economy has been somewhat limited. Looking at other items identified by the BOJ, and the differences are starker still: China isn't getting left behind by globalisation and IT (quite the reverse, as the DeepSeek story has illustrated), while the domestic cost base isn't inflated and the currency isn't appreciating. As for the deflationary mindset, state firms might choose to prioritise employment, but the vast private sector won't.

All told, on my scoring I'd suggest China is currently failing at Japanification, achieving a mark of only 30%. The scorecard is shown below, and there's also a chart pack which gives details of how China compares.

Of course, this is subjective. I haven't tried to apply any weighting: perhaps demographics, which in China if anything look worse than in Japan, will trump everything else. And, Japan's 1990s experience might not be the only path to "Japanification". China's debt stock today is bigger than Japan's in the 1990s. The ongoing difficulties at Vanke warn that problems in the property market might still take yet another turn for the worse.

Still, the differences with Japan's experience look to me to be enough to have market implications. The reason the BOJ wrote its long report was to discuss the implications for monetary policy. And in Japan, another reason why deflation was so hard to beat is because growth slowed so much, with the natural rate of interest rate falling below zero, that conventional monetary policy became ineffective. For all the problems China has, it is unlikely that real potential growth has fallen that far. And if prolonged deflation also isn't as big a likelihood as is often imagined, then a 10-year CGB yield of just 1.6% starts to look really rather too low.